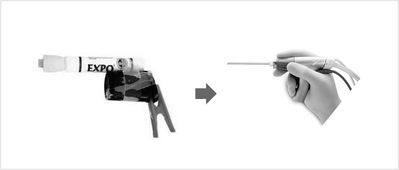

Perhaps nowhere is the art of making more celebrated than at renowned design and innovation firm IDEO. There is a huge focus on making ideas tangible. Designers learn through the process of making itself, and often the only way to help clients grasp brand-new concepts is to actually build them. The photo above shows an early-stage prototype and final design for a surgical device. The first prototype was formed by taping together a dry erase marker, a 35 mm film canister, and a plastic clothespin. Creating a physical object to hold allowed the design team to consider the how the device would feel in the hand of the surgeon, and how the power cord could best be kept out of the way. Andrew Burroughs, the engineer at IDEO who came up with the surgical device prototype, has this to say: “The prototype almost built itself – it was a quick physical expression of an idea exploring an alternate approach to laying out the parts. It wasn’t a ‘design’ as much as it was a way to explore whether the idea had any merit. Once something's out of your head and in your hands, you can pass it around for reaction.” Making an idea real turns a murky abstraction open to misinterpretation into something that can be engaged with in a very vivid way using all the senses. Chicago-based manufacturing executive Allan Evavold says it this way: “If a picture is worth a thousand words, a sample is worth a thousand pictures.” IDEO has found that often the only way to help a client or consumer understand a new-to-the-world concept, whether for a product, a service or a space, is to translate it into a physical experience.

We humans make sense of the world by interacting with it. The focus on hands-on materials and learning through doing is perhaps what Montessori schools are best known for. The method makes use of very specific, carefully crafted materials for the children to use. Children are not taught through passive listening, but rather through active engagement with these objects in the environment. A set of materials called the Golden Beads teaches children about the four basic mathematical operations. Children each roll out a small rug on the floor, and carry with them a tray with a small dish. The tray holds single beads, bars of ten, squares of 100, and cubes of 1,000 beads. Work begins with a teacher asking students to represent a particular number with their beads, say 4,276. Children walk over to what is known as the bead “store” or “bank” which contains the Golden Beads, and assemble the amount corresponding to their given number. In this case, 4 thousand-cubes, 2 hundred-squares, 7 ten-bars, and 6 unit beads. They carry these over to their small rug, count what they have brought, and correct any errors. The teacher then announces the math operation to be performed that day, such as addition. A group of children (typically just three children have a lesson at a time) bring all their beads to the large rug where their beads are combined, grouped and exchanged. Rather than having a concept described, the children accomplish the action with their own movements. Similar actions with these materials teach the children about multiplication, subtraction and division. The hands-on, active Montessori method is distinct from the conventional approach of sitting at a desk and grappling with abstractions as a teacher jots figures on a whiteboard. In Montessori schools, as in innovative workplaces, understanding derives from activity and engagement: we make sense by making things.

© 2013 Pam Daniels. All rights reserved.

We humans make sense of the world by interacting with it. The focus on hands-on materials and learning through doing is perhaps what Montessori schools are best known for. The method makes use of very specific, carefully crafted materials for the children to use. Children are not taught through passive listening, but rather through active engagement with these objects in the environment. A set of materials called the Golden Beads teaches children about the four basic mathematical operations. Children each roll out a small rug on the floor, and carry with them a tray with a small dish. The tray holds single beads, bars of ten, squares of 100, and cubes of 1,000 beads. Work begins with a teacher asking students to represent a particular number with their beads, say 4,276. Children walk over to what is known as the bead “store” or “bank” which contains the Golden Beads, and assemble the amount corresponding to their given number. In this case, 4 thousand-cubes, 2 hundred-squares, 7 ten-bars, and 6 unit beads. They carry these over to their small rug, count what they have brought, and correct any errors. The teacher then announces the math operation to be performed that day, such as addition. A group of children (typically just three children have a lesson at a time) bring all their beads to the large rug where their beads are combined, grouped and exchanged. Rather than having a concept described, the children accomplish the action with their own movements. Similar actions with these materials teach the children about multiplication, subtraction and division. The hands-on, active Montessori method is distinct from the conventional approach of sitting at a desk and grappling with abstractions as a teacher jots figures on a whiteboard. In Montessori schools, as in innovative workplaces, understanding derives from activity and engagement: we make sense by making things.

© 2013 Pam Daniels. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed